A few months back, Survival International released new photos of an uncontaminated group from the Perú border area. As usual, I sat with my mouth agape breathing in these stills of people just doing their thing against a bright, verdant backdrop. A man walks through a banana tree grove. Three fellas with hunting gear converse. Everyone looks wonderful and healthy. The kids are pudgy. The works. The kids look like they have some wonderful nightmare fuel from the plane and the older fellas seem to have taken a “oh that thing again” stance. Business as usual in the Amazon.

A few months back, Survival International released new photos of an uncontaminated group from the Perú border area. As usual, I sat with my mouth agape breathing in these stills of people just doing their thing against a bright, verdant backdrop. A man walks through a banana tree grove. Three fellas with hunting gear converse. Everyone looks wonderful and healthy. The kids are pudgy. The works. The kids look like they have some wonderful nightmare fuel from the plane and the older fellas seem to have taken a “oh that thing again” stance. Business as usual in the Amazon.

I suppose that would have been that: I would have leered, fetishized, exoticized, or claimed purely professional anthropological interest, whatever it is I am doing when photos like this come out. I would have sent them on to friends who wondered why I was freaking out (again) and then I would have sat around ashamed of myself without really understanding why. Fine, until then the news dropped that Survival International had a video. Billed as the first high quality film of an uncontacted group, they released it the next day:

Wow.

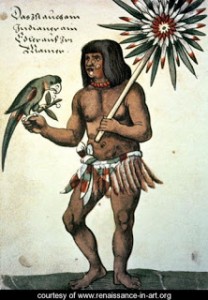

It makes me feel like a Conquistador. That is my feeling of intrigue and shame. This film may be the most spectacular bit of moving picture that I have ever experienced, and when I was first able to make out the fellow pointing at the camera from amongst the trees, I thought “this was what it was like.” It is 1532 and these people are looking at me with curiosity, misunderstanding, and disbelief and I am returning the same.

It makes me feel like a Conquistador. That is my feeling of intrigue and shame. This film may be the most spectacular bit of moving picture that I have ever experienced, and when I was first able to make out the fellow pointing at the camera from amongst the trees, I thought “this was what it was like.” It is 1532 and these people are looking at me with curiosity, misunderstanding, and disbelief and I am returning the same.

The shame comes from feeling excited by this contact experience because I know it all goes wrong in the end. I know it is not possible to have the glorious two way flow of cultural knowledge that exists in my dream contact situations: where everyone says hello, swaps stories, then stays out of each others’ lives. I feel guilty for pretending.

I take a similar guilty pleasure in reading both Conquest-era Spanish chronicles and truly terrible early Amazonian ethnographic works…and trust me I swallow those whole whenever I can find them, especially the Conquest-era accounts. I find myself ignoring atrocities so that I might enjoy the bits and pieces of Maya (or Inka or whoever) daily life and culture that I can squeeze out of them. Which is fine! It is the past and there is nothing to be done about it.

But these people are not in the past: they are out there doing their thing right now and I am peering through the trees at them. It makes me feel so strange, but I am convinced I am not dehumanizing them. Rather, I am superhumanising them and fantasizing about meeting them in some unlikely/impossible equal-footing scenario. I have gone ahead and set one of these images as my desktop background. Now I am not looking at them, they are looking at me.

But these people are not in the past: they are out there doing their thing right now and I am peering through the trees at them. It makes me feel so strange, but I am convinced I am not dehumanizing them. Rather, I am superhumanising them and fantasizing about meeting them in some unlikely/impossible equal-footing scenario. I have gone ahead and set one of these images as my desktop background. Now I am not looking at them, they are looking at me.

Suffice to say the amount of time I spend on the concept of uncontacted people has trickled into other things I have been working on. For example in the ol’ dissertation, in discussing the different Indigenous groups of Bolivia, I felt compelled to mention the 500 (give or take) uncontacted people in the Bolivian lowlands in the same sentence where I mention that something like 5+ million Bolivians identify as Aymara or Quechua.

Feed

Feed Follow

Follow